[ad_1]

Free and fair elections, the foundation of our democracy, face an unprecedented array of threats as the next one approaches. While some of these threats are well-known, others go largely unnoticed, with potentially serious consequences. Among the latter is a dangerous attempt to persuade one of our financial regulators to essentially authorize gambling on election results.

You might expect such a question to be answered by the Federal Election Commission, the agency with the expertise, history and authority to regulate elections. But a financial services company in fact petitioned an obscure financial regulatory agency to allow betting on elections through the commodities market, a prospect that could unleash a torrent of misinformation and harm investors for no discernible purpose.

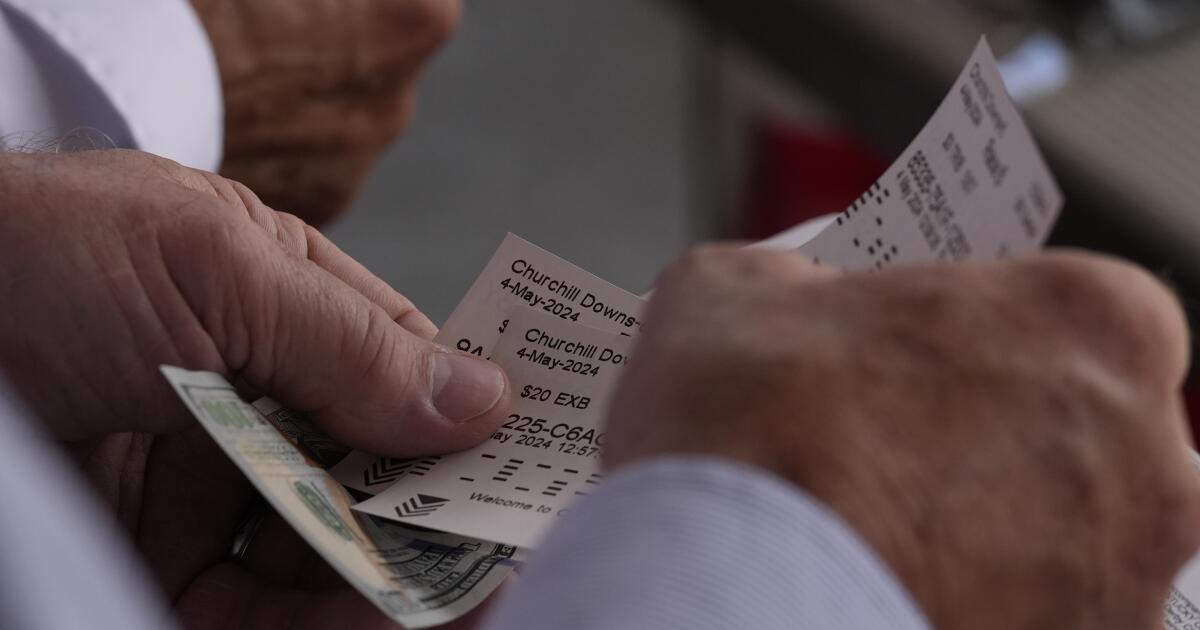

The company, Kalshi, asked the Commodity Futures Trading Commission to approve public trading of a so-called event contract that would allow investors to gamble up to $100 million on which party wins control of the U.S. House and Senate in November. The commission rightly rejected the proposal last fall, but the saga is hardly over. In keeping with the financial industry’s standard playbook, the company has sued the financial regulator, hoping a court will overturn the agency’s experts and allow it to open a virtual election casino.

The stakes of the case, which is expected to be argued in federal court in Washington this week, are high. First and foremost, the ability to “win” tens or hundreds of millions of dollars gambling on elections would create powerful new incentives for bad actors to influence voters and manipulate the results to favor their bets. Artificial intelligence “deepfakes” and other technological tools for doing so are readily available, increasingly inexpensive and primed for distribution via social media.

Just a few months ago, AI robocalls impersonating President Biden targeted New Hampshire primary voters in an effort to suppress turnout. We will undoubtedly see more such tactics before November, and enabling huge financial investments in the outcome would only supercharge them, with potentially dire consequences for our democracy.

The idea of gambling on elections is not new. Ahead of the 2012 contest between President Obama and Mitt Romney, betting on the outcome through the Ireland-based Intrade site led many observers to believe the Republican challenger was favored to win. On closer examination, however, it turned out that a single bettor had wagered large sums of money to falsely prop up Romney.

Beyond the threat to democracy, election gambling has the potential to harm investors on a large scale. The rising prevalence of constant access to markets via game-like smartphone apps, advertising campaigns full of celebrity faces and deepfake misinformation will entice more Americans into risky bets. These technologies have the potential to generate speculative investment crazes that cost investors dearly, as we saw during the “meme stock” frenzy of 2021.

Increasing addiction to cryptocurrency trading and sports gambling shows the danger of expanding these kinds of activities. And the threat to investors would grow as betting options inevitably expand from congressional control to other federal, state and local races.

Election gambling contracts pose additional financial risks. Untethered to any fundamental values, these markets would be exceptionally easy to manipulate and hard to police, further endangering unwary investors. The information that determines the pricing of the contracts would be a hodgepodge of unregulated, opaque unscientific sources such as polls and media reports that vary widely in rigor and reliability. The “house” setting the odds and others bent on profit would likely be able to selectively compile, skew and deploy data to manipulate prices.

And all for what? These contracts would serve no useful purpose. The commodities markets, which were originally limited to trading futures contracts for traditional commodities such as crops, livestock and precious metals, have steadily grown to encompass more abstract “commodities” such as futures on stock market indices. Event contracts are the latest phase of this evolution, and while some of them serve a useful function in the markets, the political gambling contracts at issue in this case simply do not.

The contracts are not reliable tools for hedging against price fluctuations or pricing the essential goods that Americans rely on, which is what the commodities commission is supposed to regulate. As the smallest and least-funded U.S. financial regulatory agency, the commission should remain focused on policing the multitrillion-dollar commodities and derivatives markets, not attempting to oversee the electoral process.

For more than 200 years, the courts have emphatically and consistently warned of the unique societal harm that could come with corruption of the electoral process through gambling. Congress has also recognized the extraordinary danger posed by this idea, which is no doubt why it authorized the commodities commission to prohibit such contracts. The commission was right to say no, and for the sake of our democracy, the federal courts should too.

Dennis Kelleher is a co-founder and the president and chief executive of Better Markets. Lisa Gilbert is the executive vice president of Public Citizen.

[ad_2]

Source link